Documentary photographs need an accompanying text or commentary to provide a context. Narrative on its own is capable of telling what looks like the whole story: images illustrate the narrative. The immediacy of documentary photographs “depends largely on our awareness that the situation they describe is ongoing” (1)

Documentary photography seems to have the same aims as the BBC – to inform, educate and entertain. This is why it has traditionally concentrated on what is foreign, unusual or strange. Much of National Geographic’s output seems to belong in this category.

Documentary may also place the photographer at the centre of the story so that it becomes a form of reportage, especially when it is concerned to draw attention to a social or political situation. When this is the case, however, the written text takes precedence over the image perhaps especially when the text is provided by someone other than the photographer. For example see Kerouac’s introduction to Robert Frank’s The Americans (2)

“THAT CRAZY FEELING IN AMERICA when the sun is hot on the streets and music comes out of the jukebox or from a nearby funeral, that’s what Robert Frank has captured in these tremendous photographs taken as he traveled on the road around practically forty-eight states in an old used car (on Guggenheim Fellowship) and with the agility, mystery, genius, sadness and strange secrecy of a shadow photographed scenes that have never been seen before on film”

In reportage the text is paramount. The images attempt to show the truth behind the opinions expressed in the text. Jacob Riis’ How the Other Half Lives is a prime example. He said of the New York slums, “The sights gripped my heart until I felt I must tell of them or burst” (3) This kind of reportage continues today. For example, see Nathan Meyer’s report on Cambodia. (4)

Photojournalism has largely been superseded by television.

Art photography is planned in advance to create particular effects. In the 1850s photographers like Julia-Margaret Cameron planned their images in the same way as painters planned theirs.

I Wait. Julia-Margaret Cameron

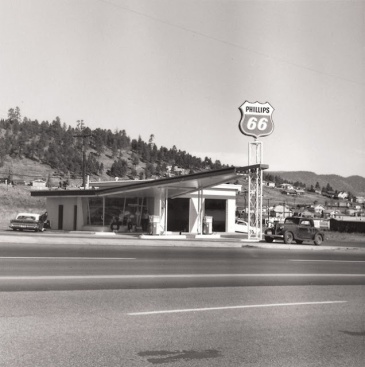

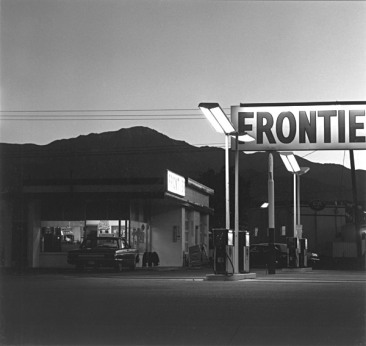

Other images achieve the status of art because of their rarity. Edward Steichen’s The Pond is such an image being bought and sold for large sums of money at art auction. Yet others achieve that status by being placed in an artistic environment, on the wall of a gallery for example, or in an art book. Some images, like this by Robert Adams

are simple records of places. While others, like this by Ed Ruscha

are intended as works of art. “In the case of Adams, it could be said that his work is ‘about’ gas stations, whereas, in the case of Ruscha, it is about the notion of objectivity, and is therefore part of an artistic discourse”. (5) In other words, the image is about whatever the author says it is about as long as they keep control over the environment the image appears in. The context proclaims the work as art and says that the author is an artist. Such images say more about the artist than about the world.

(1) Grundberg, A. (1999) Crisis of the Real (3rd ed.) Aperture.

(2) http://www.americansuburbx.com/2011/01/theory-photographer-in-beat-hipster.html

(3) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EACoIbokOcc

(4) http://reportage.co.uk/#/a-country-in-shadows

(5) Badger, G. (2007) The Genius of Photography: How photography has changed our lives. London: Quadrille Publishing Ltd. 211

The same cannot be said of this photo of Jose Mourinho. It’s not clear which of the three people is the subject of the shot. The text ‘anchors’ the meaning and fixes Mourinho in the frame.

The same cannot be said of this photo of Jose Mourinho. It’s not clear which of the three people is the subject of the shot. The text ‘anchors’ the meaning and fixes Mourinho in the frame.